La Web ha multiplicado nuestra capacidad de obtener información, pero también se incrementaron las posibilidades de que dicha información sea falsa. Economía, política, desastres naturales, guerras… nada escapa a la manipulación constante del material digital relacionado. Tal vez el origen de un texto sea más complicado de comprobar, pero si te cruzas con una imagen o un vídeo y hay algo que no te cierra del todo, existen diferentes herramientas para establecer su autenticidad.

Cómo saber si una foto es falsa o ha sido trucada

Atentados

«recientes» que jamás sucedieron, inundaciones con imágenes publicadas varios años atrás, zonas de guerra que pertenecen a países diferentes… la lista sigue. ¿Por qué alguien decide

distribuir información falsa? Las razones son muy variadas, y van desde lo sencillo hasta lo muy complejo. Las épocas de elecciones son particularmente ácidas en este aspecto, con candidatos que estimulan y financian a sus

ciber-seguidores para atacar vía

redes sociales y otros medios alternativos a sus rivales directos. La falta de escrúpulos en la distribución de información falsa obliga al usuario a convertirse en detective, debiendo comprobar el origen de cada imagen y cada vídeo que acompaña a un artículo, un reporte o una acusación. ¿Cómo podemos saber si una historia viral,

está llena de bacterias…?

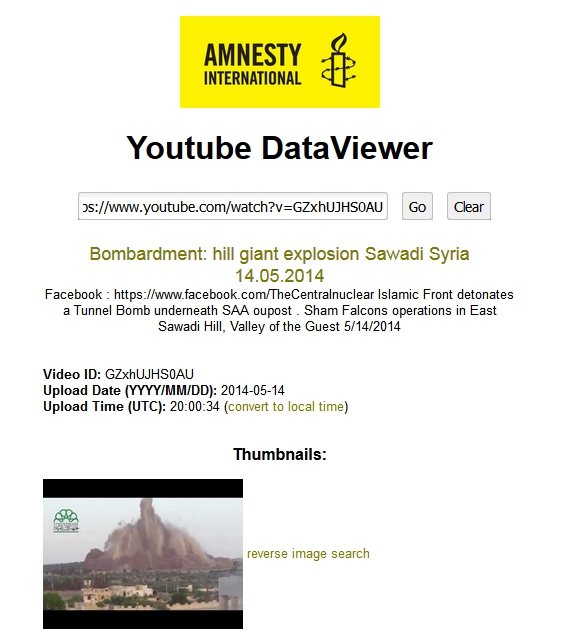

DataViewer es ideal para trabajar con vídeos

Amnistía Internacional mantiene al servicio YouTube Data Viewer, cuyo objetivo es analizar aspectos de un vídeo como la fecha de carga y las vistas en miniatura. Si estás viendo el vídeo de un bombardeo o un atentado, y la historia no ofrece ningún contexto adicional, DataViewer te ayudará a comprobar que el vídeo sea de ese lugar o evento, y no una copia con un falso título. Al mismo tiempo, las vistas en miniatura se pueden usar de otro modo…

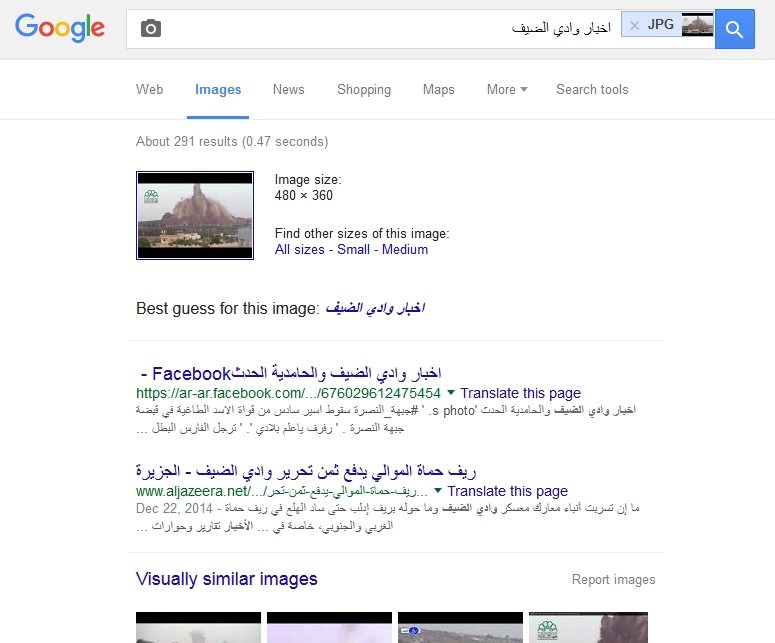

Búsqueda invertida de imágenes

Google Images es más poderoso de lo que aparenta

Gracias a la magia del Photoshop y otras herramientas similares, alterar imágenes es más sencillo que nunca, lo que permite brindar sustento a todo tipo de historias falsas. Por suerte, la misma tecnología que ayuda a la proliferación de imágenes falsas también nos permite detectar su mentira gracias a servicios de búsqueda invertida como

Google Images y el famoso

TinEye. Si una historia «nueva» utiliza fotos alteradas de 2012 tomadas en otro continente, bueno… no queda mucho por agregar.

Los análisis de niveles de errores son un poco complicados de interpretar, pero eso no altera su utilidad

La calidad de una sesión de Photoshop depende directamente de la habilidad de su usuario, y en manos de maestros, los resultados pueden llegar a ser impresionantes. Sin embargo, el ojo entrenado siempre logrará encontrar algo «extra» si los algoritmos son los adecuados. En septiembre de 2011 hablamos sobre

el portal Image Error Level Analyser, y hoy encontramos a

FotoForensics, una especie de sucesor espiritual con las mismas capacidades. Interpretar los resultados no es del todo sencillo, pero una vez que sabemos en dónde mirar, pocas cosas logran escaparse.

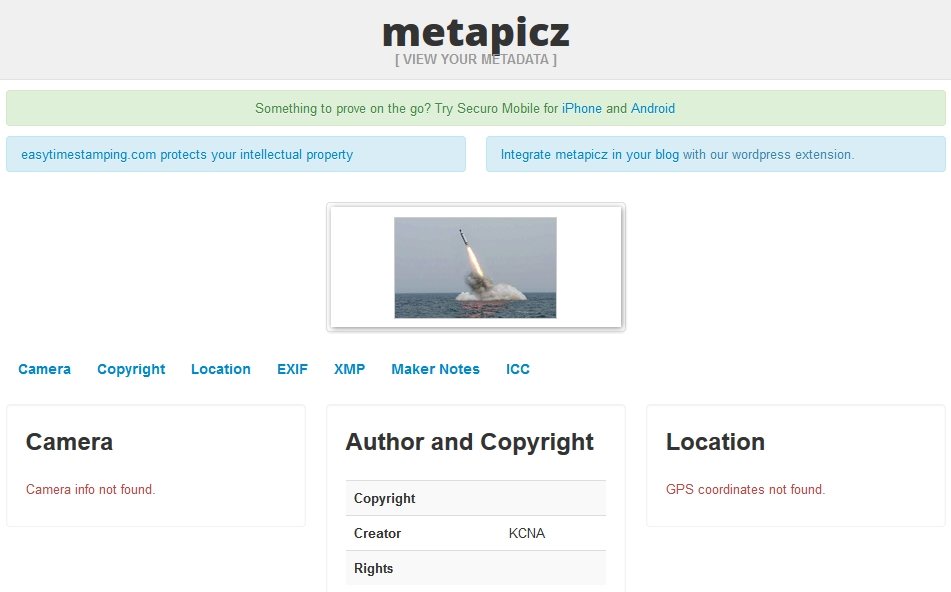

Geotags y datos EXIF

No importa si es local o en línea, siempre hay que tener a mano un lector EXIF

Casi toda cámara y smartphone tiene la capacidad de generar metadatos adicionales sobre una imagen, que no sólo indican aspectos esenciales como la configuración básica de la cámara, sino también la ubicación estimada. Si existen datos de geolocalización disponibles, nada mejor que volcarse a servicios de mapas (

Google Maps,

Yandex Maps,

Wikimapia, etc.), introducir las coordenadas y comprobar que sea el lugar correcto.

Los datos EXIF pueden ser leídos con múltiples

herramientas (locales y online), pero la mayoría de las redes sociales los eliminan por cuestiones de seguridad.

Algo tan simple como una lluvia puede delatar a una imagen. Deja que WolframAlpha te ayude.

Para cerrar, digamos que estás viendo una imagen, la cual muestra un clima muy específico. ¿Realmente había en esa fecha una lluvia torrencial capaz de inundar casas y negocios? Lo mejor es preguntarle a WolframAlpha. La clásica herramienta orientada a operaciones matemáticas también es capaz de presentar información histórica sobre el clima en diferentes regiones del globo. Si tienes el día, la hora y el lugar, lo más probable es que WolframAlpha posea la información. ¡Buena suerte!

Fuente: Neoteo.